Liouville number

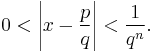

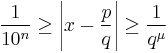

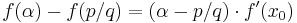

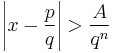

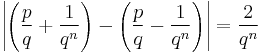

In number theory, a Liouville number is a real number x with the property that, for every positive integer n, there exist integers p and q with q > 1 and such that

A Liouville number can thus be approximated "quite closely" by a sequence of rational numbers. In 1844, Joseph Liouville showed that all Liouville numbers are transcendental, thus establishing the existence of transcendental numbers for the first time.

Contents |

Elementary properties

An equivalent definition to the one given above is that for any positive integer n, there exists an infinite number of pairs of integers (p,q) obeying the above inequality.

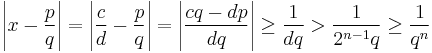

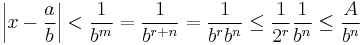

It is relatively easily proven that if x is a Liouville number, x is irrational. Assume otherwise; then there exist integers c, d with d > 0 and x = c/d. Let n be a positive integer such that 2n − 1 > d. Then if p and q are any integers such that q > 1 and p/q ≠ c/d, then

which contradicts the definition of Liouville number.

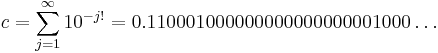

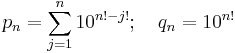

Liouville constant

The number

is known as Liouville's constant. Liouville's constant is a Liouville number; if we define pn and qn as follows:

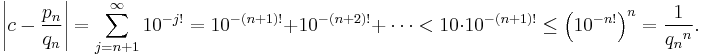

then we have for all positive integers n

Uncountability

Consider, for example, the number

- 3.1400010000000000000000050000....

3.14(3 zeros)1(17 zeros)5(95 zeros)9(599 zeros)2...

where the digits are zero except in positions n! where the digit equals the nth digit following the decimal point in the decimal expansion of π.

This number, as well as any other non-terminating decimal with its non-zero digits similarly situated, satisfies the definition of Liouville number. Since the set of all sequences of non-null digits has the cardinality of the continuum, the same thing occurs with the set of all Liouville numbers. Moreover, the Liouville numbers form a dense subset of the set of real numbers.

Liouville numbers and measure

From the point of view of measure theory, the set of all Liouville numbers  is small. More precisely, its Lebesgue measure is zero. The proof given follows some ideas by John C. Oxtoby.[1]:8

is small. More precisely, its Lebesgue measure is zero. The proof given follows some ideas by John C. Oxtoby.[1]:8

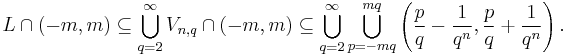

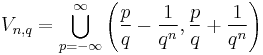

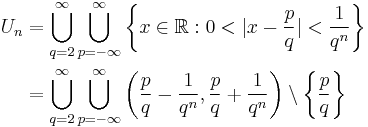

For positive integers  and

and  set:

set:

– we have

– we have

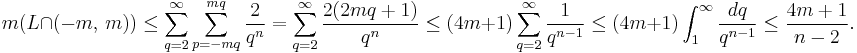

Observe that for each positive integer  and

and  , we also have

, we also have

Since  and

and  we have

we have

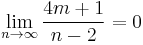

Now  and it follows that for each positive integer

and it follows that for each positive integer  ,

,  has Lebesgue measure zero. Consequently, so has

has Lebesgue measure zero. Consequently, so has  .

.

In contrast, the Lebesgue measure of the set  of all real transcendental numbers is infinite (since

of all real transcendental numbers is infinite (since  is the complement of a null set).

is the complement of a null set).

In fact, the Hausdorff dimension of  is zero, which implies that the Hausdorff measure of

is zero, which implies that the Hausdorff measure of  is zero for all dimension

is zero for all dimension  .[1] Hausdorff dimension of

.[1] Hausdorff dimension of  under other dimension functions has also been investigated.[2]

under other dimension functions has also been investigated.[2]

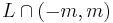

Liouville numbers and topology

For each positive integer n, set

.

.

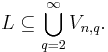

The set of all Liouville numbers can thus be written as  .

.

Each  is an open set; as its closure contains all rationals (the {p/q}'s from each punctured interval), it is also a dense subset of real line. Since it is the intersection of countably many such open dense sets,

is an open set; as its closure contains all rationals (the {p/q}'s from each punctured interval), it is also a dense subset of real line. Since it is the intersection of countably many such open dense sets,  is comeagre, that is to say, it is a dense Gδ set.

is comeagre, that is to say, it is a dense Gδ set.

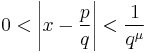

Irrationality measure

The irrationality measure (or approximation exponent or Liouville–Roth constant) of a real number x is a measure of how "closely" it can be approximated by rationals. Generalizing the definition of Liouville numbers, instead of allowing any n in the power of q, we find the least upper bound of the set of real numbers μ such that

is satisfied by an infinite number of integer pairs (p, q) with q > 0. This least upper bound is defined to be the irrationality measure of x. For any value μ less than this upper bound, the infinite set of all rationals p/q satisfying the above inequality yield an approximation of x. Conversely, if μ is greater than the upper bound, then there are at most finitely many (p, q) with q > 0 that satisfy the inequality; thus, the opposite inequality holds for all larger values of q. In other words, given the irrationality measure μ of a real number x, whenever a rational approximation x ≅ p/q, p,q ∈ N yields n + 1 exact decimal digits, we have

except for at most a finite number of “lucky” pairs (p, q).

For a rational number α the irrationality measure is μ(α) = 1. The Thue–Siegel–Roth theorem states that if α is an algebraic number, real but not rational, then μ(α) = 2.

Transcendental numbers have irrationality measure 2 or greater. As an example, e has μ(e) = 2 even though e is transcendental.

The Liouville numbers are precisely those numbers having infinite irrationality measure.

Liouville numbers and transcendence

All Liouville numbers are transcendental, as will be proven below. Establishing that a given number is a Liouville number provides a useful tool for proving a given number is transcendental. Unfortunately, not every transcendental number is a Liouville number. The terms in the continued fraction expansion of every Liouville number are unbounded; using a counting argument, one can then show that there must be uncountably many transcendental numbers which are not Liouville. Using the explicit continued fraction expansion of e, one can show that e is an example of a transcendental number that is not Liouville. Mahler proved in 1953 that π is another such example.[3]

The proof proceeds by first establishing a property of irrational algebraic numbers. This property essentially says that irrational algebraic numbers cannot be well approximated by rational numbers. A Liouville number is irrational but does not have this property, so it can't be algebraic and must be transcendental. The following lemma is usually known as Liouville's theorem (on diophantine approximation), there being several results known as Liouville's theorem.

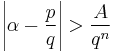

Lemma: If α is an irrational number which is the root of a polynomial f of degree n > 0 with integer coefficients, then there exists a real number A > 0 such that, for all integers p, q, with q > 0,

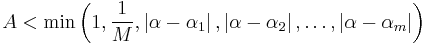

Proof of Lemma: Let M be the maximum value of |f ′(x)| (the absolute value of the derivative of f) over the interval [α − 1, α + 1]. Let α1, α2, ..., αm be the distinct roots of f which differ from α. Select some value A > 0 satisfying

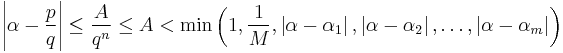

Now assume that there exists some integers p, q contradicting the lemma. Then

Then p/q is in the interval [α − 1, α + 1]; and p/q is not in {α1, α2, ..., αm}, so p/q is not a root of f; and there is no root of f between α and p/q.

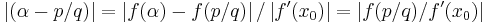

By the mean value theorem, there exists an x0 between p/q and α such that

Since α is a root of f but p/q is not, we see that |f ′(x0)| > 0 and we can rearrange:

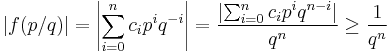

Now, f is of the form  ci xi where each ci is an integer; so we can express |f(p/q)| as

ci xi where each ci is an integer; so we can express |f(p/q)| as

the last inequality holding because p/q is not a root of f and the ci are integers.

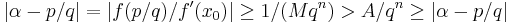

Thus we have that |f(p/q)| ≥ 1/qn. Since |f ′(x0)| ≤ M by the definition of M, and 1/M > A by the definition of A, we have that

which is a contradiction; therefore, no such p, q exist; proving the lemma.

Proof of assertion: As a consequence of this lemma, let x be a Liouville number; as noted in the article text, x is then irrational. If x is algebraic, then by the lemma, there exists some integer n and some positive real A such that for all p, q

Let r be a positive integer such that 1/(2r) ≤ A. If we let m = r + n, then, since x is a Liouville number, there exists integers a, b > 1 such that

which contradicts the lemma; therefore x is not algebraic, and is thus transcendental.

See also

References

- ^ a b Oxtoby, John C. (1980). Measure and Category. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. 2 (2nd ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-90508-1.

- ^ L. Olsen and Dave L. Renfro (February 2006). "On the exact Hausdorff dimension of the set of Liouville numbers. II". Manuscripta mathematica 119 (2): 217–224. doi:10.1007/s00229-005-0604-z.

- ^ The irrationality measure of π does not exceed 7.6304, according to Weisstein, Eric W., "Irrationality Measure" from MathWorld.